Knitting Fiction

Chapter 22: Irene, The Homework Assignment

The little bell above the yarn shop door tinkles as Irene opens it and steps into the shop. She noticed that there are only two cars in the lot. That’s because it is early afternoon. She has stopped by right after work. Straightaway, before she takes stock of the shop or caresses even a single skein of yarn, she steps up to the counter.

“Can I help you?” The woman behind the counter asks. She is tall and slender, the perfect manikin for her sweater with multiple traveling cables. Hand knit of course. Grey. Probably a mix of alpaca and silk. Stunning. Irene is momentarily distracted and then she rights herself.

“I’m Irene. I think my husband signed me up for the class about fixing mistakes,” she says.

“Let’s take a look at the roster,” and the cabled woman pulls open a drawer behind the counter and takes out a three ring binder. On the front is taped an index card, with “CLASSES” in nun-level cursive. There are multiple clear tabs marking divisions. Irene catches a quick glimpse of “BEGINNING KNIT,” “SOCKS,” and “DOUBLE KNIT” tabs. The cabled woman opens the binder at “MISTAKES.” Irene can see there are three names on the roster. The binder is upside down, but although she can’t read the names, she recognizes The Mistake’s block printing in the third grid.

“Yes, I see your class fee has been paid. The instructor happens to be in the shop right now,” the cabled woman says just as another woman walks out from behind the freestanding dividing wall of hand-dyed and hand spun yarns.

“Hi, I’m Deborah. I’ll be teaching the Fixing Mistakes class,” she says, reaching her hand to shake Irene’s.

“I’m Irene.” Irene notes that the teacher is indeed grandmother-age. The Mistake was right about that. But he was wrong about her being somehow slow or unintelligent. Behind the bifocals her eyes show interest, and she moves with energy. But then The Mistake is not entirely a good judge of character. Because he is looking for people’s weaknesses, their vulnerabilities, the ways he might exploit them, he tends to miss their strengths. When he saw Deborah as a simple, old woman, he was blind to another aspect of her. An aspect of which Irene is aware. She can sense the edges of it. Inexplicable. Something that should not quite be there, but somehow is. Irene can’t find words that fit her perception of Deborah.

“Do you have a minute? How about come back to the class area so we can visit? I want to learn more about what you would like from the class. It will help me to plan the curriculum.”

Irene follows Deborah around the shelving to an open seating area. The space is bathed in light from a solid wall of picture windows. There is a circle of seating to accommodate a dozen people, including a couch and two easy chairs. There are end tables and floor lamps with directed light and magnifiers. A center coffee table holds bowls and beer steins. In the bowls are stitch markers, measuring tapes, and needle gaugers. In the steins are knitting needles, scissors and rulers. Deborah removes a gold and red shawl from an easy chair and tosses it onto the couch. She motions Irene to have a seat in the easy chair. As Irene sits down, Deborah turns another chair toward her for conversation and sits down.

“Can I get you coffee, or perhaps tea?” Deborah motions toward a kitchen counter built in along the back wall, with a coffee maker, tea pot, and dish wear.

“No thank you.”

“Before class begins I like to get a sense of students’ goals. Is there anything in particular you would like to achieve by taking this class?”

“My Aunt Irene. I’m named after her. She left me her old aluminum knitting needles, and patterns and all of her knitting stuff. She used to call it ‘paraphernalia’.” Irene senses that she is talking too fast and too loud, but can’t seem to tone it down. “She left me all of her knitting paraphernalia.”

“I am sorry for your loss.” They sit quietly, Deborah waits a few minutes and then adds, “Oh my, want wonderful gifts you have inherited from her.”

“Yes, she used to make Alaskan Sweaters. Do you know what those are?”

“I certainly do. The designs on the sweaters are knitted intarsia style. Is that your project? To knit an Alaskan Sweater using your Aunt Irene’s paraphernalia?”

“I’ve already started. Or tried to. I started with the back and have made a mess of it.” Irene takes in a gulp of air. But then suddenly can’t seem to get enough air. She begins gasping and grabbing air and can’t seem to slow down her breathing. “I’ve made a terrible mess of it all. It’s a mess. It’s all a mess.” She inhales a ragged breath—stopping, catching, stopping catching, and then begins to sob. “I’ve made a big mistake.”

Deborah pulls her chair up closer and sits quietly beside Irene.

Irene’s face is flushed and wet with tears and snot. Between her sobs she croaks out, “I made a big mistake.”

After a few minutes Irene is able to gain control of her breathing. She forces herself to use the techniques she has learned from meditation books, breathing in through her nose and out through her mouth. Deborah pulls a box of tissue from the back of the coffee table and sets it near Irene. Still sobbing Irene pulls out sheet after sheet and begins to wipe the wet and makeup from her face. Deborah rises and retrieves a waste basket from the corner and sets it by Irene’s feet. More sobbing. More tissues. When the tears have been used up, the two women remain sitting, side by side, the one slumped and exhausted the other quiet and attentive.

Deborah speaks first, “Over the years I have learned that there are mistakes that cannot be fixed. It does not happen often, but it does happen. In these instances there is nothing for it but to frog back into nothingness. Donate the yarn to the Senior Center. Burn the pattern. Sterilize the knitting needles. Then when you are ready, begin anew. Find another pattern and buy new yarn. You are not the first woman to start over from scratch.”

“That’s what Aunt Irene said too.”

Deborah rises and drags over a large gold and red felted project bag and sets it beside her feet. She digs around in the bag and pulls out a spiral notebook with tabs. She opens it to the “Mistakes” section, then reaches for a pen from a stein. While writing in the notebook, she says, “I’ll just make a note to remind us that your goal is to right your mistake, leaving not trace left behind, and then start over.”

Deborah rests her hands in the open notebook and watches silently as Irene swipes more tissues from the box, wipes her face and tosses the tissues for the last time. She has stopped crying. They sit together in silence for a few minutes. Irene is aware of feeling comforted. No, not comforted exactly. Again, she can’t find the words. Then she does. She finds one single word. “Solid.” She is aware of feeling solid. She feels more solid than she felt before she came into the shop. More solid than she has since she began to erase herself after having made the mistake. Much later, when she recollects this day, she will add more words. Adjectives, modifiers, descriptors, whole sentences, stories and fantasies. But this will come later. Now she is aware only of her own solidity.

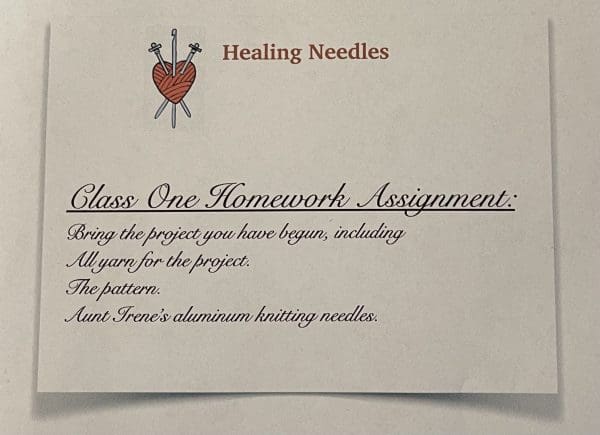

Deborah speaks first, “I’ll look forward to seeing you on Wednesday. Would you please bring your Alaskan sweater project, including all of the yarn, needles and the pattern? Bring everything you are using for that project. Also bring all of your Aunt Irene’s aluminum needles. I”m going to write that down so you remember.” Again, from the bag, Deborah pulls out a custom notepad. She writes a few lines in list format then hands it to Irene, who accepts the list and reads it.

“Will you do this?” Deborah asks.

“Yes, I will do this,” Irene responds.

Irene sits in her car. She has just left the shop and has her forearms braced agains her steering wheel. She holds her homework assignment between her two hands and studies it. Solid. The piece of paper is solid. She is solid. The car. The world. Everything is solid in way it had not been before she met Deborah. Irene knows she has just met the fourth person she can trust.