Knitting Fiction

Chapter 24: Jake, The Question

“Hey Jake, ask your mom if you can stay over on Friday.”

A boy in a grey hoodie freezes mid-hop on his way down the school bus steps, and turns toward the question. Another boy, at the top of the steps, this one in a black hoodie, twists himself around and hangs onto the front-seat pole with one hand. Dangling himself over the steps, he yells “Then we can take the ski train on Saturday morning.”

The boy on the steps smiles and tosses a thumbs up. Then he turns and in one jump clears the last two bus steps and lands with both feet, solid on frozen ground. Jake has not finished straightening from his landing and already he’s pushing his coke bottle, thick glasses back up onto the bridge of his nose. He walks fast for the first half-block, then speeds up to a trot, rocking his fully loaded backpack from side to side. Up the front steps, two at a time, then in through the front door. First, with a flick of his hand he pushes his glasses back into place and then slides out of his pack and lets it land heavy on the floor. He loosens his high tops with a single tug on the laces, slides out, and lines them up with a dozen other boots and shoes of various shapes and sizes. Remaining in his grey hoodie he slings his pack over his right shoulder and heads down the hall into the living room, at the same time yelling, “Hey Grandma.”

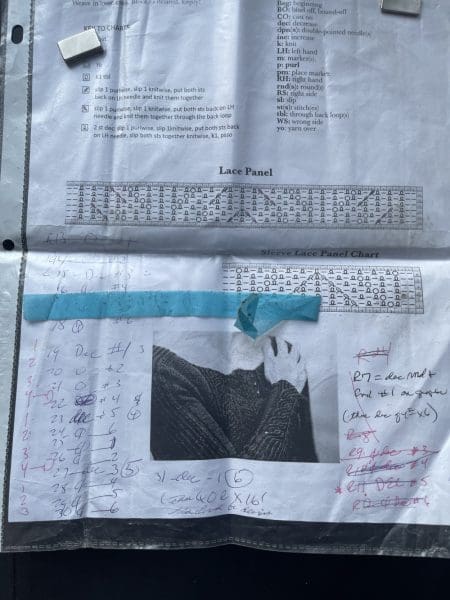

“Hey Jake,” comes the return call. She is sitting in her old blue recliner with the foot rest down. Her knitting hands quiet in preparation for his entering the living room. On her lap, against her belly, is six inches of successful lacework. Further down her lap, near her knees, is her pattern. It is inside a plastic sleeve and attached with magnets to a magnetized leather board. A magnetized ruler is placed precisely on her live instruction line. She pushes the stitches on both sides of her sharp-pointed, circular lace needle well back from the tips, where they will be safe. As she lifts her eyes from her knitting and onto the boy just entering the room, she pushes her thick lensed glasses back up and onto the bridge of her nose. At first glance, the similarity of the old woman and boy seems to end with the lenses of their glasses. At first glance. Her glasses are cat eyed, with narrow grey metal—befitting her fragile, heart shaped face. His are tortoise shell, wide and square, mirroring his square jaw. A second glance shows us, the boy stretching his neck just a hair’s breath, and tilting his head slightly to the right—it’s a gesture toward curiosity. We see the old woman leaning in toward him, her head tilted ever-so-slightly to the right. Are they mirroring one another? Or perhaps the younger has learned a habit of movement from the elder? Or would an ancestry search uncover an oil painting of an English nobleman, open book upon his lap, his head tilted forward and to the right?

“I got a question,” Jake says.

“Can it wait ‘till after this row?” she asks.

“Are you working the lace row?”

“Yes and I’ve already lost my place,” she says shaking her head. “I’m hopeless.”

“No you’re not,” he says and walks around to the back of her chair where he can read her lace instructions. “Here. You are right here.” He kneels down beside her chair and with one hand points to ‘psso’ on the instructions and with the other he touches the clustered decrease stitch that is poised on the edge of her right-hand needle.

“How do you do that? You are some sort of magician.”

“No way, Grandma. It’s math. It’s all just math. When I look at the stitches, I see numbers.”

“Just like I said, you are a magician. A magician of numbers. You and numbers are friends and they talk to you. Now where am I again?”

“I can do the math part, but not the knitting part. You are a magician of the knit part,” He lays his index finger over the enlarged letters ‘K2, YO’.

“Knit two. Yarn over. Got it, thanks,” she says.

“I have a quick question for you, Grandma—can I stay Friday night with Frank and then take the ski train with his family on Saturday?”

“Nice try, Jake. You figured that because I’m counting lace you could slip one over on me. But I wasn’t born yesterday. You already know the answer Jake-My-Boy.”

“Yeah, I know. It’s a Mom-question. ‘Wait ‘till your Mom gets home.’”

“Exactly.”

“You’ll put in a good word for me, right?”

“I’ll consider it. Now get upstairs: it’s time for your Zoom class.”

“Okay. Hey Grandma Margaret . . . .”

“I know. I already know. Yes, you can take your class in my library. I baked some cookies. Grab one, along with a glass of milk on your way upstairs.”

“Thanks Grandma. Catch you later,” he says walking past her.

“Knit two, yarn over, knit one,” she speaks out loud as she translates symbols into words, in preparation for immortalizing them with hand movements.

He sets his backpack on the floor in front of the fridge, and slugs down milk straight out of the carton. They are both smiling. He in the kitchen. She in the living room. She is eighty. He is fourteen. And they are smiling, because they both know, that she knows, that he is drinking milk straight from the carton. Then he simultaneously slings this backpack over his shoulder while grabbing a couple of cookies. At the bottom of the stairs he pauses a moment and looks at her chairlift parked in its recharging station. He takes the stairs two at a time. Down the hall and he stops at the closed door with an ornate brass plaque. It reads Grandma’s Library.

Inside, there are floor to ceiling bookshelves built into all four walls. Jake is held by books. In the center of the room stands a tapestried winged chair. He slides its matching ottoman to the side and rolls in a laptop desk. Still standing, he opens the laptop and signs into his Zoom link. While he waits for the moderator to open the Zoom room, he peruses books. He chooses three, all from different sections of the shelving. From her philosophy shelves, which comprise one entire wall, he chooses. Schopenhauer. From the biology shelves he chooses Harari. He begins to move toward fiction. Then hesitates. Takes another step. Hesitates again. Openhanded, like a blind child, he feels along the spines of McCarthy’s books. With McCarthy he must be careful which book he chooses. Not Blood Meridian. He’s not allowed. He is only allowed to read All The Pretty Horses. He has no problem obeying what Grandma calls her “Cormacian rule’. That’s because, unknown to her, he devoured The Road two years ago while she attended one of her philosophy conferences. McCarthy gave imagery and words to Jake’s fears. He had just finished The Road, when Grandma returned, and the chairlift was installed. That’s when Jake’s nightmares began. He has told no one of his dreams. Not his parents, not his best friend, and certainly not Grandma. Instead, in his dreams, he stands alone in dark and empty places. Desperately searching for his caretaker. She has been taken away. Or has she left him? No, she’s been taken away, leaving him alone and unprotected in the aftermath.

His hand moves across Cormacian spines but comes to rest on The Cambridge Companion to Cormac McCarthy. He slides it out from the shelf and places all three books on the arm of the chair. Seated, he opens them to random pages and reads. After class Jake replaces the desk and ottoman, but leaves the books. He knows his grandmother will pick up each book and read a few pages before she returns them to their correct places on the shelves.

He then goes to his room, retrieves his violin and music stand and returns to the library. Once inside, he carefully closes the door and practices. After taking his violin and music stand back to his room, he tosses his backpack over his shoulder, closes the library door and heads for the stairs. He takes his time. The stairs are his decompression chamber. As he descends, he leaves behind the quiet of the library and moves toward robust kitchen sounds. When he reaches the bottom of the stairs, he pauses, and turns towards Grandma’s stairlift. It remains mostly in its recharging station, because she only uses it when she needs to carry something up to her rooms. If she does not have to carry anything, she can hold on to the handrails and take the stairs on her own. Even though he knows she is in the kitchen, his mind’s ear can hear her say, “Slow and steady.” That’s what she says when climbing the stairs, “Slow and steady.’

Jake takes one step into the kitchen, hits a wall of sensation, and instantly rebounds, and takes his step back. Then rebounds again, back into the kitchen—into bright LED lights and yellow walls. Five family members are in the room, taking up space, making sounds. His mother sits at the kitchen table focused on her laptop—no doubt answering last minute emails before dinner. Grandma Margaret and the twins sit across from her amidst books and papers strewn about. The eight year old girls, Zoe and Chloe, are fighting and whining.

“Nooo you left the door open.”

“Nooo, it was you. You left the door open.”

“That’s you, what about me?”

“I’m rubber. You’re glue.”

Dad turns away from the stove where he is stirring spaghetti sauce, and yells toward them “Alright you girls, quiet down.”

“But Zoe started it.”

“Oh for heaven’s sake,’ his mother says. She pauses her fingers and raises them up above her laptop keyboard. She has paused her hands, but does not look up from the screen as she says, “Oh for heaven’s sake. Paul, can’t you do something?”

Dad rallies, “I don’t care who started it.” He steps away from the stove, wooden spoon still in hand, and takes a few steps toward the kitchen table. The girls cross their arms and turn away from each other. Leaving an opening for Jake.

He walks deep into the kitchen, opens a cupboard door and takes out the colander and sets it in the sink. Standing beside his father at the stove, Jake takes a hot pad from the counter and places it on the handle of the sauce pan filled with boiling noodles. “Hey Dad, I have a question for you,” he says as he carries the noodles to the sink.

Jake’s dad turns toward him, “Thanks, Jake. What’s your question?”

“Can I spend the night on Friday with Frank? His family is going to take the Ski Train on Saturday. They have an extra ticket for me. He said they will come and pick me and my gear up on Friday after school and then drop me off at home on Saturday when we get back.” Jake lets the noodles slide into the colander and then places noodles, colander and all into the serving bowl.

His father removes the skillet with red sauce from the stove and comes to stand beside Jake at the counter. “The Ski Train? That sounds like fun. I don’t see why not,”

He says while pouring the sauce into a matching serving bowl. “We gotta run it by your Mom first though.”

Just then Grandma stands and announces to everyone, “It looks like supper is done. We need to set the table. You girls pick up your homework. We’ll work on spelling after supper.”

Jake’s mother stands, replaces her laptop into her briefcase and sets it aside. “I’ll set the table.” She looks toward Grandma Margaret, who is still helping the twins organize their school papers. “Ma, do you have any thoughts about the Ski Train?”

“I think it is a terrific idea–with one caveat.”

“What’s that?” Jake’s mother asks. Jake and both his parents look toward Grandma Margaret. The twins stop what they are doing and also look toward the old woman.

Jake’s “Oh no.” is subvocal, but somehow Grandma hears him.

“Hold on Jake. You don’t have to lawyer up”

Grandma makes eye contact with Jake’s dad. “Paul, you know as well as I do that Frank’s mom, Chrissy likes her drink.”

“Oh no, hear it comes,” Jake is shaking his head.

Grandma’s glasses have slid down her nose. She looks at Jake over the top of them, for a moment before pushing them back up. “Hold on to your horses, Jake,” she says.

Then she turns back to Jake’s dad, “Paul, everyone knows the Ski Train culture includes partying and drinking.”

Jake is turning away and groaning.

“All I’m saying is this. Paul, I think you ought to talk directly to Steve, Frank’s dad. Tell him you do not want the boys drinking alcohol.”

Here she turns back to Jake, “That means no jello shots. That means no funny brownies.”

“Geez, Grandma.”

Jake’s dad breaks in, “No, your grandmother is right. I’ll talk to Steve and make sure he keeps an eye on the boys.”

“We’re settled then?”, Jake’s mom asks.

Jake’s dad says, “We’re settled. I’ll talk to Steve. Jake will spend the night with Frank on Friday and take the Ski Train with them on Saturday.”

“Thank God," Grandma Margaret says. “That means I can give that Ski Train ticket back to Ida.”

Jake’s mother begins to laugh, “Ma, you are so bad. You are a bad grandma.”

Jake says, “You wouldn’t have done that! You wouldn’t have taken the Ski Train just to keep an eye on us?”

“Don’t be too sure,” Grandma says.

They are seated around the table and beginning to pass the serving bowl of noodles when Jake’s mother says, “Hey Ma, now that we have the Ski Train question answered. I have another one for you. How did your visit with Dr. Krauss go today?”